During the uprisings that swept Tunisia and Egypt in 2011, digital activists’ main adversary were their governments which, in the case of the former, censored scores of websites and conducted man-in-the-middle attacks on Facebook users and, in the case of the latter, shut down the Internet entirely after two days of protests shook the capital.

Uprisings in other countries throughout the region–Bahrain and Syria in particular–have witnessed a different phenomenon altogether. While it’s true that both countries censor the Internet extensively, opposition activists have faced a different type of foe: propaganda from pro-regime actors seeking to shift the public narrative in their favor.

Though the use of propaganda to influence political and social actions online is no new thing–Takis Metaxas notes the use of online propaganda in the 2004 US presidential elections, for instance–a new repertoire of tactics have emerged in the past year, many of them emanating from the two countries.

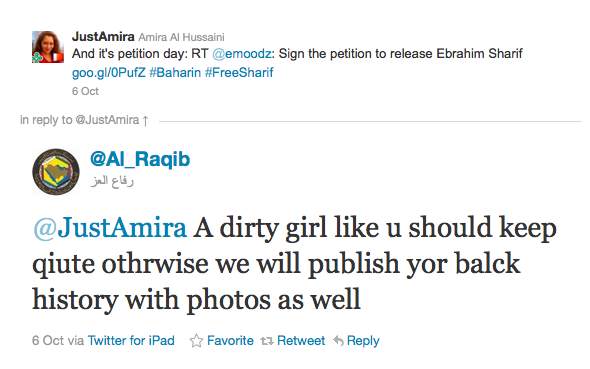

In Bahrain, online propagandists may have been assisted by American public relations firm Qorvis, as the Atlantic reported last month. The efforts of regime supporters (be they paid shills or individuals with a lot of free time on their hands) were largely focused on Twitter, where they would attack supporters of the opposition on the #Bahrain hashtag. In a piece for the New York Times Lede Blog, J. David Goodman explained:

“In the months since Bahrain’s Sunni monarchy quashed a wave of giant protests, mostly by members of the country’s Shiite majority, the government has sought to counter negative international attention, often with the help of foreign public relations agencies.

At the same time, activists and journalists have reported receiving vitriolic messages from individuals — so-called trolls — on Twitter and other social media platforms.”

Bahraini blogger Husain Yousif described also described the phenomenon, stating: “They start working and finish all together. Which means, it’s like a job. They talk about Iran, sectarian warfare — they use common words and they never discuss. They just come to fight.” Human Rights First also wrote about the Bahraini Twitter trolling.

[image 1: A Bahraini Twitter troll targets Bahraini blogger Amira al Hussaini]

[image 1: A Bahraini Twitter troll targets Bahraini blogger Amira al Hussaini]

Many accounts specifically targeted Times journalist Nick Kristof, whose investigative reporting from Bahrain resulted in his receiving death threats on the platform. Others have simply targeted anyone posting news about the country’s conflict.

In Syria, regime supporters used similar tactics, flooding the #Syria hashtag with irrelevant content early on in an effort to drown out the voices of the opposition. Later, they turned to more extreme tactics, forming the Syrian Electronic Army and hacking and defacing websites.

[image 2: A Syrian propaganda account tweeting photos of Syria emerged amidst the early days of the uprising]

As I’ve written before, when a state needs to stoop to the level of paying citizens to fight its public relations wars, it has already lost. But perhaps more interesting is the idea that, in Syria and Bahrain, unpaid citizens have joined in taking up “cyber-arms” against their foes in support of the state.